Labour Has Already Solved Asylum

It just needs to do it again.

So Rwanda is dead. Officially, I mean. It was obviously dead on arrival when it was announced two whole years ago. While the Rwanda plan saw a resurgence of support when Sunak took it up as the solution to one of his ‘five priorities’, it’s important to remember that this was not always the case. When the plan was announced, it set firmly in the context of Partygate, and was widely seen as a ‘red meat’ policy to rile up the base and win Boris some support, with statements from senior Tory MPs to this effect.

The policy not only failed to save Boris Johnson from resignation, but also failed in what it attempted to do embarrassing the government in the process. For reference, 130 people were intended to be sent on that first flight. By the time the flight was due to take off, it was down to just seven. A later intervention by the ECHR reduced that number to zero. Despite there clearly needing to be a number of lessons learned, there has never been a serious autopsy of why Rwanda failed. That topic will remain for another article, but the lack of lessons learned are important. The main take-away from figures such as Suella and Sunak has been that leaving the ECHR may be necessary. Glance back at those figures: 130 were notified they were set to be sent on that first flight, only seven were removed by the ECHR. 123 of those were removed by domestic law, and a High Court document revealed some were even removed by the then-Home Secretary Priti Patel, for reasons unknown.

The lessons learned by figures such as Matt Goodwin have been to support Rwanda because ‘it’s the only game in town’. Supporting something because it’s the only thing on offer is foolish, unimaginative, and destined to result in bad policy. Most policy suggestions are, simply put, bad. It takes willpower and a lot of boring and unsexy work to get things right. This article is the product of a lot of boring and unsexy work, including independent research. But the outcome has been a collection of data which is probably the most comprehensive on the subject until the Migration Observatory updates their page on the subject.

The Asylum Revolution

Before 1990, asylum was fairly simple. We had the Refugee Convention of 1951, which applied only to Europe, and the 1967 Protocol, which applied to the world. These two documents afforded people the right to seek asylum in any country that was a signatory. However, it was ultimately infeasible for people to come to the UK. The Channel Tunnel (1994) did not exist and Europe was still focusing on rebuilding post-World War II. Moreover, communications technology such as the mobile phone had not yet become popular. However, as the world became richer, more interconnected, and its people became more mobile - much of the world realised what they were missing out on in the West. And in 1989, many of them decided to come to the UK.

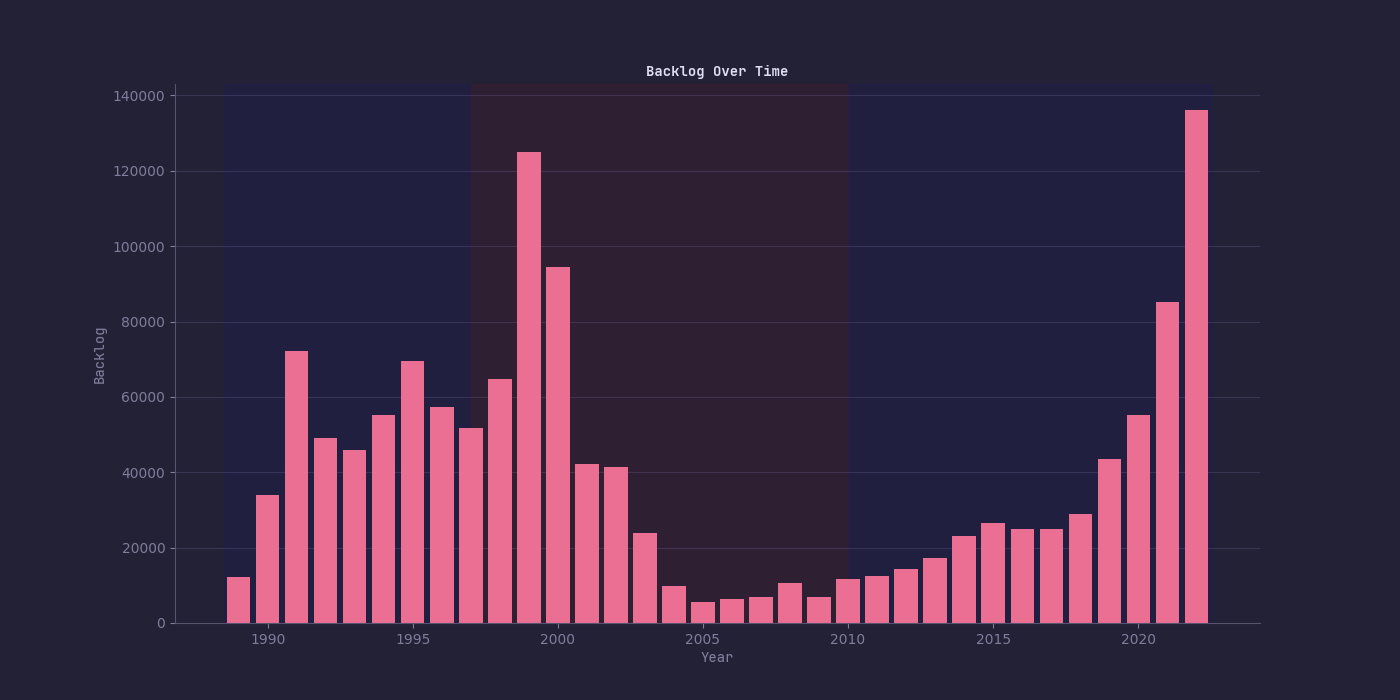

From 1979 to 1989, asylum applications per year ranged from 1563 to around 6000. The overwhelming majority of these would be accepted, with acceptance rates rates between 75-90%. In 1989 however, the applications then nearly triple to 16775. A year later, they double to 38195. Then in 1990, another year later, they nearly double again to 73400. Asylum applications have increased exponentially over these three years, and an asylum system based on principles set down three decades prior are now being tested. The Conservative government responds in the worst way possible: by secretly granting Exceptional Leave to Remain to 44% of all asylum seekers in an attempt to clear the backlog in 1992. In 1993 they repeat the feat by granting Exceptional Leave to Remain to a further 11,000. Exceptional Leave to Remain is designed for those who do not fit the definition of refugee under the Refugee Convention, but are deemed to be needing to be granted leave to remain due to ‘exceptional’ circumstances. Considering the use of Exceptional Leave to Remain, the fact the Conservatives did not announce this, and only allowed it to be discovered in the statistics - this has all the hallmarks of an attempt to clear the backlog. Alongside this, they also began rejecting asylum claims en-masse, with the acceptance rate dropping from above 80% to below 50% in just one year. Britain was being flooded with unfounded claims. Coupled with the high rate of claims and a large backlog, asylum rules prior to 1993 meant that anyone who saw a significant delay in their application would have this apply as a point in favour of approving their application. This rule had to be removed, as a number of unfounded claims were approved as they had been waiting a long time for their claim to be reviewed.

By 1996, one year prior to election, the Conservative government passed yet-more legislation. This time to cut benefits to asylum seekers. Home Office documents suggest this had a minor effect on reducing claimants but the main effect was to further alienate the Conservatives from many London constituencies. As most asylum applicants arrived via plane, they tended to land in Heathrow. As a result, most asylum claimants ended up in London boroughs and changing the local communities. By stripping them of their benefits, many asylum seekers became destitute. A 1996 court ruling then found that local authorities would have to provide them with the benefits the central government refused to provide. The Conservative policy of granting ELR to rid themselves of the backlog, and cut the benefits in an attempt to dissuade people had ultimately caused many London boroughs to inherit large populations of homeless asylum seekers the local councils were now responsible for looking after.

How New Labour Solved Asylum

Against this backdrop, New Labour came to power. Tony Blair appointed Jack Straw to solve the growing asylum issue. The increased rejection rate had seen the numbers drop from 73400 in 1991 back down to 32300 in 1992, but the trend was towards increasing numbers of asylum seekers, not less.

In July 1998, Fairer, Faster, and Firmer was published by Jack Straw, outlining the plans for asylum under New Labour. Central to this was the consideration of the asylum and immigration systems being viewed as one and the same. Contemporary politics discusses legal and illegal immigration as separable, but ultimately the two are intertwined. A person who wishes to enter the country legally will do so illegally if entering illegally is easier, and vice-versa. Consequently, Fairer, Faster, and Firmer tackled both the asylum and immigration systems, which saw the introduction of the following into the asylum system:

A single management structure, the Joint Entry Clearance Unit, to handle visa entry clearance.

New technologies, such as fingerprinting, and entering the UK into Eurodac – an EU-wide system for tracking migrants, and entering the Dublin Conventions (signed 1990, came into effect 1997.) A new computer system for handling asylum would be introduced, moving away from paper technologies.

Shifting of the responsibility for looking after asylum seekers from local councils to the Home Office.

Crackdown on immigration advisors who made money from legal aid.

Removal of appeal to upper courts.

The Immigration Nationality Directorate was restructured, and moved to a system of integrated caseworking.

The IND hired 500 new caseworkers, and targets focused on speed.

This centralised approach to asylum was coupled with a streamlining of the rules. The 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act created the ‘One Stop Appeal’. Many claimants would make multiple separate claims in order to delay their removal for as long as possible. The One Stop Appeal meant that you must state all grounds to remain in the country in application, and any further grounds would not be considered. These changes could not have come soon enough. In 1999 the number of total applicants hit a record high of 91,200. They would stay at 98,000 in the year 2000. Then 91,600 in 2001. And then, in 2002, the asylum system would reach its peak of 103,081 applicants. This is a figure unmatched, even today. And yet, the Labour government dealt with it.

The IND moved quickly, going from 27000 initial decisions in ‘98/99 to 52000 initial decisions in ‘99/00 and then to 132840 decisions in ‘00/01. They rejected to overwhelming majority of applicants. To dissuade illegal migration, they established Oakington Detention Centre in the year 2000. The detention centre was used for a process known as ‘Detained Fast-Track’, where if an application was judged to be able to be resolved quickly - the subject would be detained in Oakington with roughly half having their case decided in two months. Most of these would be refusals. A review in 2012 found roughly 93% of all claims in Oakington were refused, and in Q1 of 2003, Oakington received 1210 cases and made decisions on 1085 of them - all refusals.

These measures: fast decisions, high rejection rate, detention for obvious fraudulent claims, limiting the avenues of appeal to just one and only entertaining one claim solved asylum. They created a system which saw a backlog of 125,100 in 1999 (slightly less than our current peak of 136,233) cut down to 5500 in just 6 years. If this is not the measure of solving asylum, then what is?

Conclusions

So will Labour do this now? I think they will. One measure I didn’t mention here was that New Labour also had crack teams going out and actively preventing traffickers from leading groups of people onto flights. This stopped tens of thousands of people ever reaching the UK. Starmer looks to be proposing a similar solution for those leading dinghies out off the coast of France. This is a much smaller area to have to control (one coastline vs. every airport.) If the traffickers change tactics to planes, he may well just implement the previous solution. Considering Blair is almost certainly advising Starmer behind the scenes, it’s inevitable he’ll pick up some of the lessons from the Blair period. Moreover, Starmer is a human rights lawyer. He knows the rights of asylum seekers, and he knows what he can and cannot get away with.

Starmer’s main issue is ignoring the many NGOs, Quangos, and activist groups who will try and prevent any kind of migration control. The incoming Labour government has already shown an appetite for ignoring entrenched interests in the pursuit of its goals by changing the rules for onshore wind. With asylum being so prominent an issue, it’s natural that Starmer will take from Blair and solve asylum once again.