Solving the Driving Test Crisis

What's causing the 5-month waits for test, and how to solve it.

Britain has a driving test crisis. The current wait time for tests is 17.4 weeks as of December 2023, up from 7.8 weeks in 2016. In January of 2023, the then Transport Minister, Richard Holden, confirmed a five month delay in some areas. This singular issue is the biggest issue with learning to drive today. Where once you may have been able to rebook a test for next week, the backlog of driving tests is a compounding issue for prospective drivers. The longer the wait, the worse their driving gets, and so they require lessons to ensure they remain skilled enough to pass. This creates demand for driving instructors, who now must divide up their time between those looking to start driving, but also those waiting for tests. This has been compounded by attempts to reduce demand on tests by preventing people from re-applying for a test 28 days after they fail.

As a result, 40% of instructors have increased their prices, while 28% have removed discounts and deals on lessons. And it looks like the market has responded. Both 2022 and 2023 saw a roughly 60-70% increase in those attempted to become Approved Driving Instructors over the previous 2020 high.

So what happened with driving tests? The graph below paints a fairly obvious picture about the lasting impact of Coronavirus on driving tests. While driving tests did fall some 18.5% from their record high pre-corona, from a high of 1,762,363 in 2007 to a low of 1,436,481, on a per-capita basis they fell by 21.8% in 2012.

While I try to find less simplistic answers to questions in this publication, sometimes the simple solution is the correct one. The driving test crisis really is caused by the lasting effects of Coronavirus. The only real evidence to the contrary is the slow, declining number of tests post-2010. Even then, this looks to be more a question of demand rather than anything else. The number of tests conducted increases post-2020 once we leave the European Union, and the supply of Light Goods Vehicle drivers is limited. The number of tests conducted shoots up as private enterprise begins to raise salaries for drivers, and so people became LGV drivers. If we were limited on capacity to test, we would expect to see a slight bump to signify demand but limited tests being conducted.

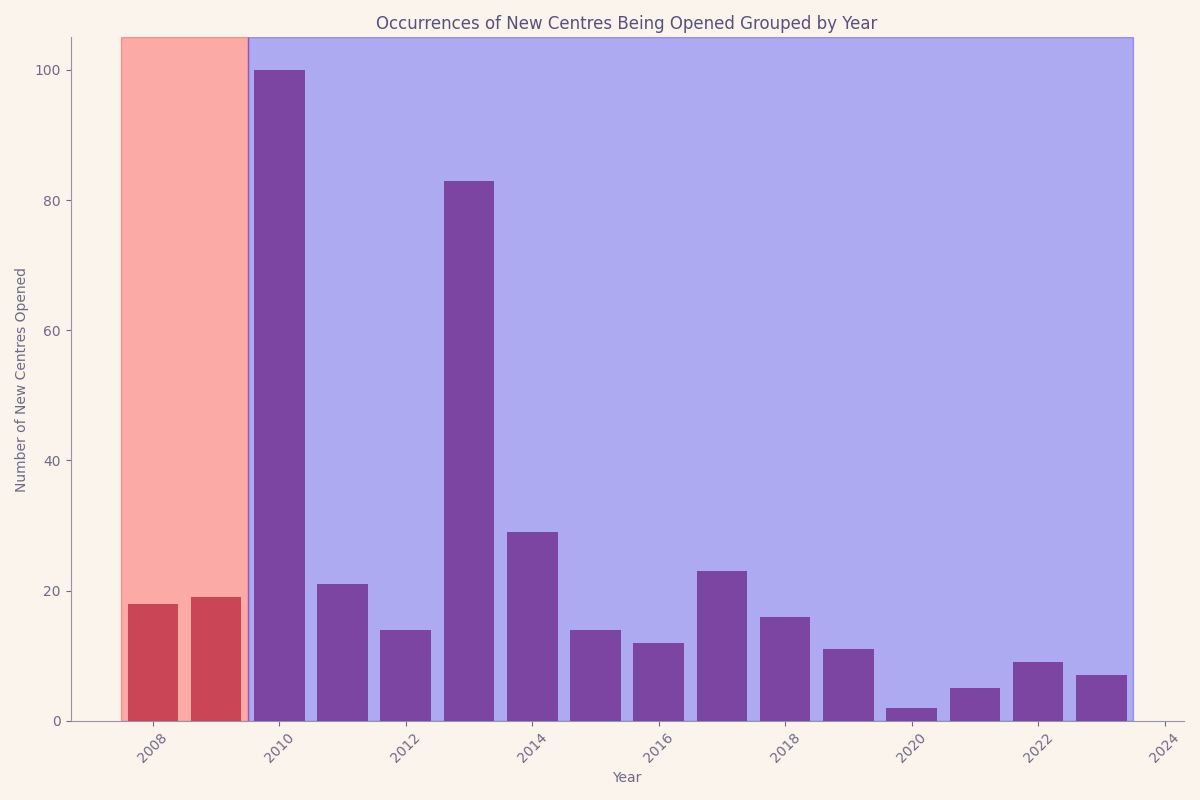

Astute readers will note the post-2010 dip is when the Conservatives got into power, and so I wondered if driving test centres were being closed down under the austerity of the period, so I found each centre which was marked as closed in the data and logged the last year in which it was actively performing tests.

Surprisingly, the number of closures carried out by Labour between 2007 to 2010 was 54, and between 2010 to 2023, the number of closures carried out by the Conservatives was 64. We can also find the number of new centres by recording when new centres appear in the data. Using 2007 as a reference, between 2008 and 2010, Labour opened 34 centres. In contrast, the Conservatives opened 346 centres in 2010 and beyond.

Take these figures with a grain of salt. If locations are renamed, this would count as a closure and an opening. Moreover, two years of Labour data isn’t particularly thorough. Regardless, there’s little evidence of austerity measures impacting the DVSA, this is likely because it was run as a Trading Fund, a government department that operates basically like a business. Under Labour, it was run as the Driving Standards Agency. It was then folded into the DVSA in 2014 under the Conservatives. Under Labour, DSA ran fairly efficiently, with a turnover of £184m (£278m in 2024) into 2009 and suffering a deficit of just £8m for that year (which is attributed in their reports to the weather and economic conditions.) Reading a report from 2008 to 2009, we can see that the DSA actually ran a modest surplus for most of the early noughties.

This table also paints an obvious picture. Until 2008, DSA ran a modest surplus. Post-2008, DSA ran a deficit. The most obvious answer being that the 2008 financial crash turned consumers away from unnecessary spending, and the DSA became one such casualty. Ten years later, in 2018 to 2019, the DVSA ran much more inefficiently, with a £58m deficit and expenditures at £448m with revenues at £399m. Costs are up nearly 50%, and yet less tests are being performed and potential drivers are being saddled with the costs of extra lessons and long wait times to get a test.

I began this article hoping to find some secret sauce to solving the driving test crisis, and perhaps point to factors that may have been missed in the obvious damage of Coronavirus, or find some other country doing things differently and better. In reality, there’s little reason to blame any political party or individual. The story of the DSA and DVSA is as boring as a story about the institutions in question would suggest: We had a modestly profitable government department, a wonderfully rare and nice thing to have, which was made unprofitable by the financial crash. It then ran a deficit for a further decade until it was made into just another government department in 2021. That same year, it had to severely limit operations due to a pandemic, and has been playing catch-up ever since.

Into that void, private companies have sprung up to resolve the issue. Websites and applications such as Testi and Driving Scout will crawl DVSA for new tests, and then provision them quickly to students at their desired times. Instructors are now block booking tests for their students in an attempt to get them preferable times, and if you’re sad enough to read the comment sections of DVSA announcement posts – other instructors are claiming some even sell these more convenient tests at higher prices. Anyone who has booked a driving test understands how annoying the process can be, with anti-bot measures making it difficult for legitimate users to use the service – which makes the bots which can evade the measures even faster at booking tests.

The boring solution to this boring problem about a boring department is fairly simple: make the IT services better, and clear the backlog. The former could be done by simply embracing the private sector standards for provisioning tests: students enter the times and days they’d like a test, and they’re provisioned a test in that bracket when it becomes available. As for the backlog, this could be solved by opening new test centres and hiring more examiners (who will become unionised, most likely) or by evading the unions, hiring privately and using them to clear the backlog. This would be unlikely to be worthwhile politically, however. Disempowering unions is not always popular, and it doesn’t play well politically, and clearing the driving test backlog is not a public priority.

On that note, if you’ve read this far – you’re probably within the < 1000 people in the UK who is both interested in politics, and interested in the boring details of issues such as this. So while the driving test backlog will likely slowly close up over time, it will pass unmarked by the political climate of the country at large.